São Paulo Governor Imports Police Violence from Rio

Paulistas elected an outsider to govern their state. Now Tarcísio de Freitas, a neofascist retired Army Captain, is encouraging his cops to emulate Rio de Janeiro’s worst tactics.

By Brian Mier

In 2013, while I was working as assistant producer for BBC’s documentary series Welcome to Rio, military police special forces from the BOPE squadron chased two suspects into one of the favelas in the Complexo do Mare, where we were filming with a local community leader. During the shoot out that followed, a police officer was killed. The next day the BOPE drove into the favela in armored vehicles and assassinated 10 people in a revenge killing spree. Some of the people killed were low level workers in the recreational drug trade. However, during the operation, two BOPE agents snuck into a random middle-aged couple’s house and stabbed them to death in their sleep.

One year later, working as an interpreter on Vice/HBO’s The Pacification of Rio, I mentioned the stabbing incident to the presenter, Ben Anderson, who had ample experience working in the Middle East.

“That is a classic counterinsurgency tactic,” he said. “The Israeli army uses it in Palestine all the time. It’s done to create a mood of terror in the community.”

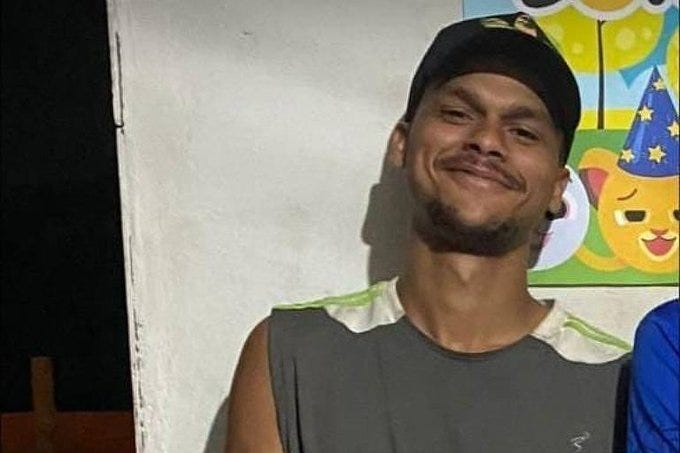

On July 27th after a member of the São Paulo Military Police special forces ROTA squadron was killed in a favela in the coastal city of Guaruja, police began a multi-day operation invading favelas in the region which has left at least 16 people dead. Among the victims was assistant bricklayer Layrton Fernandes da Cruz Vieira de Oliveira, 22 who was murdered by police in his sleep. They also killed his dog.

With 16 deaths, it was the worst police massacre in the state of São Paulo since the Carinduru prison massacre of 1992. It also represents a troubling shift in policing approach under Governor Tarcísio de Freitas, one of neofascist former President Jair Bolsonaro’s closest allies, who only moved to São Paulo after winning the state gubernatorial elections.

In Brazil, the military police – a dictatorship holdover who’s members aren’t regulated by the civilian court system – are ostensibly controlled by state governors. There isn’t a state in the union that doesn’t have a problem with police killings, torture and summary executions, primarily of black male youth. Rio de Janeiro, however, is a case apart. Whereas in the United States, an average of 37,000 arrests are made for every police killing, during the first decade of the 21st Century Rio de Janeiro police caused 1 death per 23 arrests. This number is outrageous, even by Brazilian standards. By comparison, during the same time period São Paulo police killed one person for every 348 arrests – a terrible statistic in it’s own right, but 15 times lower than the figure from Rio de Janeiro.

There are several reasons why Rio de Janeiro is the worst state in Brazil for police violence. Only one organized crime group, the PCC, controlls nearly all of the favelas in the huge São Paulo metro area, which comprises about half of the state population. In Rio there are three factions constantly engaged in armed conflict with each other, the Commando Vermelho, the Terceiro Commando Puro and the Amigos dos Amigos. In addition, a large part of the favelas are controlled by right wing paramilitary militias led by off duty or former military police officers, including the Escritorio de Crime, which controlls a group of favelas on the West Side including Rio das Pedras and which has strong ties to the Bolsonaro family. For example, Flavio Bolsonaro employed the wife and mother of Escritorio de Crime leader Adriano Nobrega in his state congressional cabinet for over a decade, and their hit-man Ronnie Lessa, who is currently in jail for murdering Marielle Franco and her driver Anderson Gomes, was a neighbor of Jair Bolsonaro in a luxury condominium complex.

All three drug trafficking factions and the militias have infiltrated Rio de Janeiro’s military police to it’s highest level, and over the years, there have been multiple occasions where police have rented their personnel and their armored vehicles to help one faction invade the territory of another.

Another difference between Rio and the rest of the country is that the typical standard issue police weapon is a fully automatic assault rifle like the Israeli IWI Tavor X95. In other states, police normally patrol with revolvers and the occasional shotgun, with assault rifles normally only regulated to the special forces troops, which are holdovers from the dictatorship era military death squads.

Whereas the São Paulo police have a notorious reputation for using intelligence to locate, illegally kidnap and execute their targets – always getting the “right” person – Rio de Janeiro police are notorious for opening fire with fully automatic rounds and asking questions later, frequently killing innocent bystanders like the toddler who was killed in the Muda neighborhood I lived in when police accidentally opened up machine gun fire on the wrong car.

São Paulo governor Tarcísio de Freitas is a retired Army Captain who, like most of Jair Bolsonaro’s closest allies, studied at the elite Agulhas Negras military academy which is known for being a hotbed of formation of the fascist tigrada internal faction of the armed forces that pines for the return of the military dictatorship that ended in 1985. Under the most famous living tigrada leader, former Bolsoanro intelligence chief General Augusto Heleno, he worked as an army engineer in the Minustah occupation in Haiti during the period of the Cité Soleil massacre. At the time of the Minustah occupation, General Heleno was criticized in Brazil for attempting to implement Rio de Janeiro military police tactics in Port-au-Prince – namely patrolling the rich and middle class neighborhoods and leaving the poor to fend for themselves, periodically going into slums guns blazing in attempts to assassinate gang leaders. After the Cité Soleil massacre, President Lula removed Heleno from Haiti, and he has been a sworn enemy ever since.

During last year’s election season Workers Party gubernatorial candidate Fernando Haddad warned voters about the danger of electing someone a “puppet of Jair Bolsonaro” who couldn’t even name the neighborhood his hastily assembled São Jose de Campos residence was located in, but he was ignored by the majority of the voters, especially in the extremely conservative interior of the state, which is home to nearly 20 million people. They also ignored when Freitas’ bodyguards allegedly murdered an unarmed Afro-Brazilian man during a campaign stop in Paraisopolis favela, in order to create a mediac event to show that he was tough on crime.

For decades, human rights activists in Brazil have been fighting to eliminate the military police entirely. The Workers Party has tried to pass constitutional amendments 3 times to disband the military police, most recently through a bill submitted by then Senator Linbergh Farias (RJ) in 2013 Each time, the measure was blocked by conservative coalition partners in a context in which the PT has never elected more than 25% of the seats in Congress or the Senate.

Today, these state police organizations are hard to control, but there are governors who do what they can to reduce police violence through measures such as making officers wear body cameras and opening investigations after massacres take place. Then there are governors like Freitas who green light police violence by trying to eliminate body cameras and publicly defending the police when they commit human rights violations, as he did

The last Brazilian governor to openly encourage police executions was Wilson Witzel in Rio de Janeiro, who went as far to try to install snipers at the entrances of favelas to assassinate low level drug dealers. “Aushwitzel” as he was nicknamed, was forcibly removed from office and arrested. Does the same fate await Tarcísio de Freitas?

Originally published on Substack

If you enjoyed this voluntarily-produced article, please consider making a small donation through Paypal (paypal.me/BrianMier2019)