Nayib Bukele and the Myth of Popular Support in El Salvador

Written by Roberto Zapata and Camila Escalante in late 2021 for Lumpen Magazine’s Spring 2022 International Issue.

Nayib Bukele’s improvised political experiment has given rise to a new dictatorship in El Salvador. Although in the beginning he was profiled as a youthful, social media savvy and alternative face, Bukele’s Nueva Ideas administration rapidly turned down a path of authoritarianism, centralizing power, promoting militarism as a main state policy, and banning any type of criticism against his government.

Despite this, Bukele’s groupies in the mainstream foreign press insist that he remains popular among Salvadoran youth. Until recently it was hard to find challenges to this claim. Now, at the halfway mark in his term in office, it is clearer than ever that young people are faring poorly. Thousands of young Salvadorans continue to flee the country each month, while those who stay are becoming increasingly involved in mobilizations and activism to oppose the government’s neoliberal, authoritarian measures.

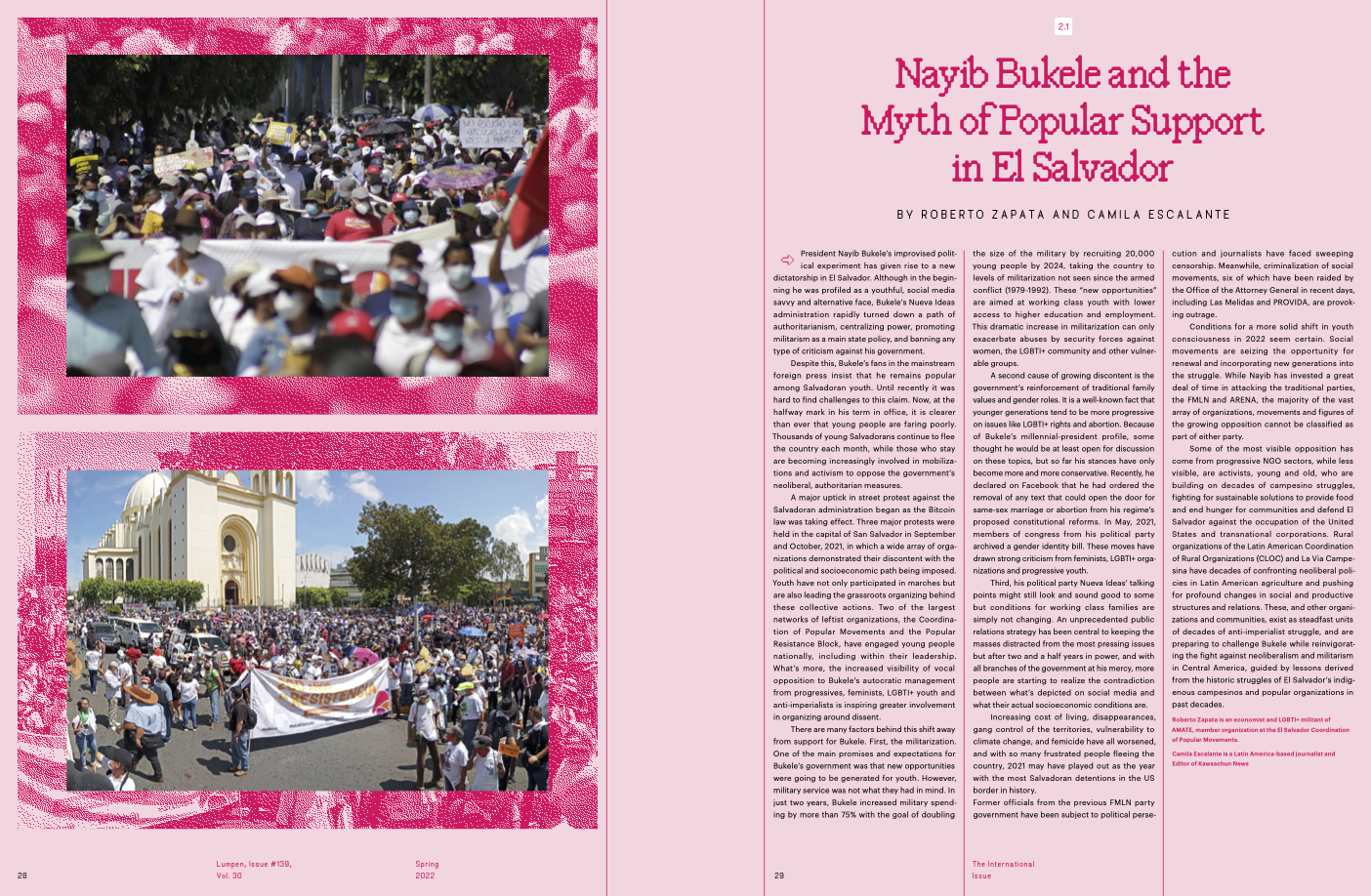

A major uptick in street protest against the Salvadoran administration began as the Bitcoin law was taking effect. Three major protests were held in the capital of San Salvador in September and October, 2021, in which a wide array of organizations demonstrated their discontent with the political and socioeconomic path being imposed.

Youth have not only participated in marches but are also leading the grassroots organizing behind these collective actions. Two of the largest networks of leftist organizations, the Coordination of Popular Movements and the Popular Resistance Block, have engaged young people nationally, including within their leadership.

What’s more, the increased visibility of vocal opposition to Bukele’s autocratic management from progressives, feminists, LGBTI+ youth and anti-imperialists is inspiring greater involvement in organizing around dissent.

There are many factors behind this shift away from support for Bukele. First, the militarization. One of the main promises and expectations for Bukele’s government was that new opportunities were going to be generated for youth.

However, military service was not what they had in mind. In just two years, Bukele increased military spending by more than 75% with the goal of doubling the size of the military by recruiting 20,000 young people by 2024, taking the country to levels of militarization not seen since the armed conflict (1979-1992).

These “new opportunities” are aimed at working class youth with lower access to higher education and employment. This dramatic increase in militarization can only exacerbate abuses by security forces against women, the LGBTI+ community and other vulnerable groups.

A second cause of growing discontent is the government’s reinforcement of traditional family values and gender roles. It is a well-known fact that younger generations tend to be more progressive on issues like LGBTI+ rights and abortion. Because of Bukele’s millennial-president profile, some were under the impression that he would be at least open for discussion on these topics, but so far his stances have only become more and more conservative.

Recently, he declared on Facebook that he had ordered the removal of any text that could open the door for same-sex marriage or abortion from his regime’s proposed constitutional reforms. In May, 2021, members of congress from his political party archived a gender identity bill. These moves have drawn strong criticism from feminists, LGBTI+ organizations and progressive youth.

Third, the talking points of his political party Nueva Ideas might still look and sound good to some but conditions for working class families are simply not changing.

An unprecedented public relations strategy has been central to keeping the masses distracted from the most pressing issues but after two and a half years in power, and with all branches of the government at his mercy, more people are starting to realize the contradiction between what’s depicted on social media and what their actual socioeconomic conditions are.

Increasing cost of living, disappearances, gang control of the territories, vulnerability to climate change, and femicide have all worsened, and with so many frustrated people fleeing the country, 2021 may have played out as the year with the most Salvadoran detentions in the US border in history.

Former officials from the previous FMLN party government have been subject to political persecution and journalists have faced sweeping censorship. Meanwhile, criminalization of social movements, six of which have been recently targeted in raids by the Office of the Attorney General, including Las Melidas and PROVIDA, are provoking outrage.

Conditions for a more solid shift in youth consciousness in 2022 seems certain. Social movements are seizing the opportunity for renewal and incorporating new generations into the struggle.

While Nayib has invested a great deal of time in attacking the traditional parties, the FMLN and ARENA, the majority of the vast array of organizations, movements and figures of the growing opposition cannot be classified as part of either party.

Some of the most visible opposition has come from progressive NGO sectors, while less visible, are activists, young and old, who are building on decades of campesino struggles, fighting for sustainable solutions to provide food

and end hunger for communities and defend El Salvador against the occupation of the United States and transnational corporations. Rural organizations of the Latin American Coordination of Rural Organizations (CLOC), the regional articulation of the international peasants movement La Vía Campesina, have decades of confronting neoliberal policies in Latin American agriculture and pushing for profound changes in social and productive structures and relations.

These, and other organizations and communities, exist as steadfast units of decades of anti-imperialist struggle, and are preparing to challenge Bukele while reinvigorating the fight against neoliberalism and militarism in Central America, guided by lessons derived from the historic struggles of El Salvador’s indigenous peoples, campesinos and popular organizations in past decades.

Roberto Zapata is an economist and LGBTI+ militant of AMATE a member organization of the Coordinadora Salvadoreña de Movimientos Populares

Camila Escalante is a Latin America-based journalist and Editor of Kawsachun News

Lumpen #139 The International Issue can be downloaded in PDF format here: